All that glitters is not “ORO”: Cantarella Bros v Lavazza

Did you know that the word “ORO” means “gold” in Italian? “Gold” is a laudatory word that would normally be difficult to register as a trade mark. In a recent trade mark infringement case, the Federal Court sought to clarify the test to determine whether a trade mark holds any “ordinary signification” (or “ordinary meaning”), which is relevant to whether “ORO” is sufficiently distinctive to be registrable.

The Court also made remarks about the concept of abandonment in trade mark law. This is a question with very little judicial guidance to date, but highly relevant to whether one person can “recycle” another person’s disused trade marks.

Background

This case concerned two giants of Australian coffee, Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd (Cantarella), and Lavazza Australia Pty Ltd with Lavazza Australia OCS Pty Ltd (together, Lavazza).

Proceedings were brought by Cantarella, who alleged that Lavazza had infringed its two registered trade marks (registration nos. 829098 and 1583290) for the word “ORO” in class 30 (which covers coffee beverages) under section 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth). The alleged infringement was due to Lavazza using the Italian word “ORO” on its coffee products and in advertising them. Cantarella argued that it was substantially identical to their marks. Cantarella is no stranger to defending its trade mark rights, with its ORO registrations the subject of many cases, including at the High Court of Australia.

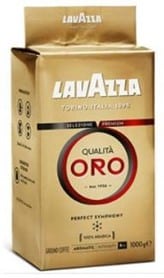

An example of Lavazza allegedly infringing Cantarella’s mark is in the below product package, where use of the word “ORO” is prominent:

Lavazza disputed that it was using the word “ORO” as a trade mark and also brought a cross-claim arguing that both of the Cantarella trade marks should be cancelled for the following reasons:

- that each mark was not inherently adapted to distinguish Cantarella’s goods from the goods of others; and

- that Cantarella was, in any event, not the true owner in Australia of the “ORO” word mark as it pertains to coffee.

Was Lavazza using the word “ORO” as a trade mark?

Lavazza argued that use of the word “ORO” on its packaging was purely descriptive of the quality of the coffee and that this did not constitute use as a trade mark. Notwithstanding this, Justice Yates agreed with Cantarella that Lavazza was using the word “ORO” as a trade mark, reiterating the principle that use of a word in relation to goods or services can still function as a trade mark even though it has a descriptive element.

While noting that “ORO” was not the dominant feature of the product packaging, the Court still considered it to be one of the dominant features. Despite the word “QUALITA” being used above “ORO”, the Court was satisfied that the word “ORO” could function as a trade mark in its own right. Interestingly, Justice Yates also concluded that although other traders in the coffee space had used the word “ORO” for their products, this did not preclude it from being used as a trade mark. The Court also found that common use of a particular word in a particular trade, such as a coffee, would not hinder it from functioning as a trade mark.

Even though Lavazza was using “ORO” as a trade mark, the Court did not need to make a detailed determination on available defences. That was because Cantarella’s trade marks were not validly registered (more on that below). Regardless, Justice Yates did note that each of the defences raised by Lavazza would have failed.

Were Cantarella’s trade marks inherently adapted to distinguish?

In determining whether a trade mark is inherently adapted to distinguish the goods or services of one trader from another, Justice Yates considered:

- whether the trade marks hold an “ordinary signification” to those who would purchase, consume or trade in the goods or services; and

- having determined the “ordinary signification”, the likelihood of the mark being desired for use by other traders in the ordinary course of business, without improper motive, upon or in connection with their goods or services.

Justice Yates determined that the word “ORO” did not hold “ordinary signification” in Australia, due to the belief that the public would not have recognised the word “ORO” as meaning gold. As such, it was inherently adapted to distinguish. These considerations had previously been raised in the High Court Canterella decision, and Justice Yates took care not to disturb those findings.

Were Cantarella’s trade marks validly registered?

Lavazza argued that both of Cantarella’s trade marks were not validly registered, because another company, Caffe Molinari Oro (Molinari), first used the word “ORO”. This would give Molinari prior use that predated Cantarella’s priority date for both of their marks. Accordingly, Cantarella was not deemed to be the owner of the trade marks. Molinari was an Italian coffee producer who supplied several Australian coffee wholesalers. Interestingly, Molinari’s use of the trade mark had been considered in the High Court Canterella decision, however new evidence of use was presented to Justice Yates that had not been found in the previous cases.

It is noteworthy that Molinari had no registered trade mark for the word “ORO”. Examples of packaging used by Molinari are as follows:

The concept of abandonment

In response to this argument, Cantarella argued that Molinari had abandoned its “ORO” mark. Under common law, ownership of a registered trade mark can be lost in the case of abandonment. If abandonment of a mark is proven, then the invalidity argument against Cantarella would fail. It has previously been established that such abandonment must be intentional and not “mere non-use or slightness of use” of a mark. In determining whether an intention to abandon had arisen, Justice Yates looked at the evidence presented in the case with regards to use by Molinari.

In this case, “abandonment” did not depend on whether Molinari used the word “ORO”. It clearly did. Instead, it depended on whether Molinari had used “ORO” as a trade mark, rather than simply as a descriptive term to indicate gold-quality coffee.

On reviewing the evidence provided, Justice Yates determined that Molinari had used the word “ORO” as a trade mark on several of their coffee packs. Justice Yates made this determination because of how “ORO” was used regarding the size, colour, positioning, and prominence of “ORO” on the packaging and in relation to other elements of it. Interestingly, the Court also noted that just because Molinari never attempted to register the word “ORO” in Australia, did not mean that Cantarella could make a claim of ownership over the mark.

In his decision, Justice Yates was ultimately satisfied that Molinari had used the word “ORO” sufficiently as a trade mark in Australia and so, had not abandoned it. This use was also, critically, prior to Cantarella’s first use.

Cancellation of the Cantarella trade marks

In deciding whether to cancel the two trade mark registrations, the Court held that a claim of ownership cannot depend on the nature or scope of Cantarella’s reputation in the “ORO” brand. Additionally, while the Court has observed in prior cases that use of a mark over a number of years (without causing confusion) is a relevant consideration for allowing registration, such a consideration may not hold significant weight. While both of Cantarella’s marks remain registered, it is expected that they will eventually be cancelled when both parties agree on consent orders. Regardless, Cantarella would maintain common law rights in the mark and could potentially sue for misleading and deceptive conduct under Australian Consumer Law due to their reputation.

What does this judgment mean?

Ultimately, Justice Yates determined that Cantarella’s case could not succeed because both of their trade marks were deemed invalid. Consequently, this decision brings to the forefront the need for organisations to establish ownership of a trade mark prior to alleging infringement by another party. Comprehensive searches should be undertaken before filing a trade mark to make sure there is no unregistered use that could invalidate your trade mark.

It further highlights the need to keep records of use of your brand from inception. If the evidence relied upon in this case had been available in 2014, the High Court Canterella decision may have been determined differently, and the trade marks invalidated almost 10 years earlier.

Given the history of the parties involved, it is likely that we haven’t seen the end of the battle for the “ORO” trade marks.

What MK can do for you?

If you’re unsure whether your brand’s IP is sufficiently protected, get in touch with MK’s award winning intellectual property team.

The information contained in this article is general in nature and cannot be relied on as legal advice nor does it create an engagement. Please contact one of our lawyers listed above for advice about your specific situation.

more

insights

stay up to date with our news & insights

All that glitters is not “ORO”: Cantarella Bros v Lavazza

Did you know that the word “ORO” means “gold” in Italian? “Gold” is a laudatory word that would normally be difficult to register as a trade mark. In a recent trade mark infringement case, the Federal Court sought to clarify the test to determine whether a trade mark holds any “ordinary signification” (or “ordinary meaning”), which is relevant to whether “ORO” is sufficiently distinctive to be registrable.

The Court also made remarks about the concept of abandonment in trade mark law. This is a question with very little judicial guidance to date, but highly relevant to whether one person can “recycle” another person’s disused trade marks.

Background

This case concerned two giants of Australian coffee, Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd (Cantarella), and Lavazza Australia Pty Ltd with Lavazza Australia OCS Pty Ltd (together, Lavazza).

Proceedings were brought by Cantarella, who alleged that Lavazza had infringed its two registered trade marks (registration nos. 829098 and 1583290) for the word “ORO” in class 30 (which covers coffee beverages) under section 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth). The alleged infringement was due to Lavazza using the Italian word “ORO” on its coffee products and in advertising them. Cantarella argued that it was substantially identical to their marks. Cantarella is no stranger to defending its trade mark rights, with its ORO registrations the subject of many cases, including at the High Court of Australia.

An example of Lavazza allegedly infringing Cantarella’s mark is in the below product package, where use of the word “ORO” is prominent:

Lavazza disputed that it was using the word “ORO” as a trade mark and also brought a cross-claim arguing that both of the Cantarella trade marks should be cancelled for the following reasons:

- that each mark was not inherently adapted to distinguish Cantarella’s goods from the goods of others; and

- that Cantarella was, in any event, not the true owner in Australia of the “ORO” word mark as it pertains to coffee.

Was Lavazza using the word “ORO” as a trade mark?

Lavazza argued that use of the word “ORO” on its packaging was purely descriptive of the quality of the coffee and that this did not constitute use as a trade mark. Notwithstanding this, Justice Yates agreed with Cantarella that Lavazza was using the word “ORO” as a trade mark, reiterating the principle that use of a word in relation to goods or services can still function as a trade mark even though it has a descriptive element.

While noting that “ORO” was not the dominant feature of the product packaging, the Court still considered it to be one of the dominant features. Despite the word “QUALITA” being used above “ORO”, the Court was satisfied that the word “ORO” could function as a trade mark in its own right. Interestingly, Justice Yates also concluded that although other traders in the coffee space had used the word “ORO” for their products, this did not preclude it from being used as a trade mark. The Court also found that common use of a particular word in a particular trade, such as a coffee, would not hinder it from functioning as a trade mark.

Even though Lavazza was using “ORO” as a trade mark, the Court did not need to make a detailed determination on available defences. That was because Cantarella’s trade marks were not validly registered (more on that below). Regardless, Justice Yates did note that each of the defences raised by Lavazza would have failed.

Were Cantarella’s trade marks inherently adapted to distinguish?

In determining whether a trade mark is inherently adapted to distinguish the goods or services of one trader from another, Justice Yates considered:

- whether the trade marks hold an “ordinary signification” to those who would purchase, consume or trade in the goods or services; and

- having determined the “ordinary signification”, the likelihood of the mark being desired for use by other traders in the ordinary course of business, without improper motive, upon or in connection with their goods or services.

Justice Yates determined that the word “ORO” did not hold “ordinary signification” in Australia, due to the belief that the public would not have recognised the word “ORO” as meaning gold. As such, it was inherently adapted to distinguish. These considerations had previously been raised in the High Court Canterella decision, and Justice Yates took care not to disturb those findings.

Were Cantarella’s trade marks validly registered?

Lavazza argued that both of Cantarella’s trade marks were not validly registered, because another company, Caffe Molinari Oro (Molinari), first used the word “ORO”. This would give Molinari prior use that predated Cantarella’s priority date for both of their marks. Accordingly, Cantarella was not deemed to be the owner of the trade marks. Molinari was an Italian coffee producer who supplied several Australian coffee wholesalers. Interestingly, Molinari’s use of the trade mark had been considered in the High Court Canterella decision, however new evidence of use was presented to Justice Yates that had not been found in the previous cases.

It is noteworthy that Molinari had no registered trade mark for the word “ORO”. Examples of packaging used by Molinari are as follows:

The concept of abandonment

In response to this argument, Cantarella argued that Molinari had abandoned its “ORO” mark. Under common law, ownership of a registered trade mark can be lost in the case of abandonment. If abandonment of a mark is proven, then the invalidity argument against Cantarella would fail. It has previously been established that such abandonment must be intentional and not “mere non-use or slightness of use” of a mark. In determining whether an intention to abandon had arisen, Justice Yates looked at the evidence presented in the case with regards to use by Molinari.

In this case, “abandonment” did not depend on whether Molinari used the word “ORO”. It clearly did. Instead, it depended on whether Molinari had used “ORO” as a trade mark, rather than simply as a descriptive term to indicate gold-quality coffee.

On reviewing the evidence provided, Justice Yates determined that Molinari had used the word “ORO” as a trade mark on several of their coffee packs. Justice Yates made this determination because of how “ORO” was used regarding the size, colour, positioning, and prominence of “ORO” on the packaging and in relation to other elements of it. Interestingly, the Court also noted that just because Molinari never attempted to register the word “ORO” in Australia, did not mean that Cantarella could make a claim of ownership over the mark.

In his decision, Justice Yates was ultimately satisfied that Molinari had used the word “ORO” sufficiently as a trade mark in Australia and so, had not abandoned it. This use was also, critically, prior to Cantarella’s first use.

Cancellation of the Cantarella trade marks

In deciding whether to cancel the two trade mark registrations, the Court held that a claim of ownership cannot depend on the nature or scope of Cantarella’s reputation in the “ORO” brand. Additionally, while the Court has observed in prior cases that use of a mark over a number of years (without causing confusion) is a relevant consideration for allowing registration, such a consideration may not hold significant weight. While both of Cantarella’s marks remain registered, it is expected that they will eventually be cancelled when both parties agree on consent orders. Regardless, Cantarella would maintain common law rights in the mark and could potentially sue for misleading and deceptive conduct under Australian Consumer Law due to their reputation.

What does this judgment mean?

Ultimately, Justice Yates determined that Cantarella’s case could not succeed because both of their trade marks were deemed invalid. Consequently, this decision brings to the forefront the need for organisations to establish ownership of a trade mark prior to alleging infringement by another party. Comprehensive searches should be undertaken before filing a trade mark to make sure there is no unregistered use that could invalidate your trade mark.

It further highlights the need to keep records of use of your brand from inception. If the evidence relied upon in this case had been available in 2014, the High Court Canterella decision may have been determined differently, and the trade marks invalidated almost 10 years earlier.

Given the history of the parties involved, it is likely that we haven’t seen the end of the battle for the “ORO” trade marks.

What MK can do for you?

If you’re unsure whether your brand’s IP is sufficiently protected, get in touch with MK’s award winning intellectual property team.