Battle of the beds and baths in New Zealand trade marks

Did you know that you can contest the validity of a competing trade mark if you believe the mark shouldn’t have been registered in the first place? In New Zealand, the Court or Commissioner has the power to decide whether a trade mark is invalid and therefore, should be treated as unregistered. This can be a worthy tactic for protecting your brand, but there are specific considerations that may hinder your chance at a successful outcome, as demonstrated by a recent dispute.

Bed Bath & Beyond lost its fight to have Bed Bath ‘N’ Table’s registered trade mark invalidated in New Zealand. The High Court of New Zealand handed down its decision in Brands Limited v Bed Bath ‘N’ Table Pty Limited [2023] HZHC 1766 on 7 July 2023.

Bubble, bubble, toil and trouble

Both Bed Bath & Beyond (BBB) and Bed Bath ‘N’ Table (BBT) have operated in New Zealand in parallel for over 15 years. Both brands sell furniture, linen and home décor, using similar green branding.

There were two rounds of trade mark registrations.

The first, in 1994. BBB registered the trade mark “BED BATH & BEYOND”; BBT applied 5 months later to register “BED BATH N’ TABLE” but ended up abandoning those applications.

The second, in 2014. Both BBB and BBT again applied to register their respective trade marks. By this stage, BBB had 51 stores in NZ and BBT had 9 (plus 97 in Australia). On 4 June 2014, BBT applied to register “BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE” in NZ and 5 days later BBB filed its own application for “BED BATH & BEYOND” in respect of very similar goods. Both parties’ marks were registered without opposition from the other.

The trade mark dispute commences

In 2018, BBT opposed BBB’s application to register “BED BATH & BEYOND” in Australia. Included in BBT’s evidence was a claim that the use of “BED BATH & BEYOND” would lead to consumer confusion.

In December 2018, BBB sought cancellation of BBT’s trade mark registration in New Zealand under section 73 of the Trade Marks Act 2002 (NZ), on the basis of invalidity. That is, if the trade mark should not have been validly registered, then it should not be allowed to remain on the register. Claims for trade mark infringement, passing off and fair trading claims were added in 2020, but we’ll focus on the invalidity claim here.

The invalidity claim

Under section 73, the Court, on the application of an aggrieved person, may declare the registration of a trade mark invalid to the extent that it was not registrable. Under section 74, an invalid mark is treated as if it had not been registered.

At the core of BBB’s claim was section 25(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 2002 (NZ) which discusses reasons the Commissioner should not register a trade mark in respect of any goods or services.

The core issues arising for determination under s 25(1)(b) were:

- whether BBT’s 2014 trade mark was registered in respect of goods or services that are the same as or similar to those covered by BBB’s trade mark;

- whether BBT’s 2014 trade mark was similar to BBB’s trade mark; and

- whether the fair notional use of BBB’s trade marks and BBT’s 2014 trade mark is likely to deceive or confuse a substantial number of persons in the relevant market.

Similar goods and services?

BBB could only rely on its much narrower 1994 registration rather than its broader 2014 registration which post-dated BBT’s 2014 registration. It meant that the respective goods and services being compared were:

- BBB’s 1994 registrations that covered former class 42; and

- BBT’s 2014 registration which included class 20, 24 and 35.

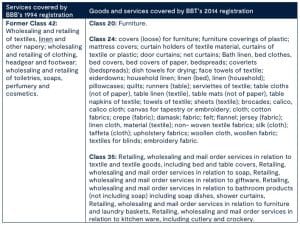

The comparison of goods and services are detailed in the table below.

In comparing these goods and services, the Court held (at para [121]) that the services in class 35 of BBT’s application and many of the goods in class 24 are similar to the services in BBB’s registration. Even though BBB’s earlier mark was only registered in relation to services, these services were still similar to BBT’s goods, much like the Australian concept of goods that are “closely related” to services.

Confusingly similar marks?

The assessment of trade mark similarity is based on “an assessment of the fair and notional use” of the trade marks, not their actual use.

The threshold for “confusion” between two trade marks is lower than “deceived”. “Confusion” may go no further than perplexing or mixing up the minds of the purchasing public, while “deceived” requires an incorrect belief.

The High Court set out the considerations, based on the earlier decision of the New Zealand Court of Appeal in Pharmazen Ltd v Anagenix IP Ltd [2020] NZCA 306 at [47]:

(a) the Court should consider the marks in their entirety; the overall or net impression of the marks should be considered;

(b) while differences between two marks may be significant, it is the similarities which are most significant, whether visual, audible, distinctive, or conceptual;

(c) the impression or idea conveyed by the marks is important in assessing how they will be recalled; the idea of a mark is more likely to be recalled than its precise details;

(d) comparison is not of the opponent’s mark with the mark of the applicant when taken side by side, but taking into account imperfect recollection in all the circumstances in which the products might be sold; and

(e) the marks are to be compared as they would be encountered in the usual circumstances of trade.”

In the words of the Court in the BBB / BBT case:

(a) both marks begin with the alliteratively memorable combination of words: “bed, bath”;

(b) in both marks, the words “bed” and “bath” are used not in a directly descriptive way (discussed further below) but in what is known as an indirectly descriptive way;

(c) in other words, each mark indirectly refers to the products sold by the trade mark owner—products for the bedroom and products for the bathroom;

(d) in BBB’s mark the words “bed, bath” are followed by “’n”, which undoubtedly signifies “and”;

(e) in BBT’s mark the words “bed, bath” are followed by “and”;

(f) in BBB’s mark the words “bed, bath ‘n” are followed by the two syllable, word “beyond”;

(g) in BBT’s mark the words “bed, bath and” are followed by the two syllable word “table”;

(h) just as the word “beyond” reinforces the alliterative flavour of the BBB mark as a whole, the second syllable of “table” (“ble”) reinforces the alliterative flavour of the BBT mark as a whole;

(i) in the context of BBB’s mark, the word “beyond” is intended to refer, and would reasonably be construed as alluding to, “goods for use in other rooms in a house”;

(j) in the context of BBT’s mark, the word “table” is intended to refer, and would reasonably, be construed as alluding to “goods for use in the kitchen and/or dining room”;

(k) reading all the words in BBB’s mark together, they convey the impression or idea of “goods for use in the home”;

(l) reading all the words in BBT’s mark together, they convey the impression or idea of “goods for use in the home”;

(m) there is therefore considerable visual (four words, the first three of which are effectively identical and in identical order) and aural (four words, the first three of which are effectively identical and the last of which has two syllables) similarity between the two marks; and

(n) the marks are likely to be encountered in similar circumstances (retail outlets operated by the parties, and the branding and advertising of the goods sold there).

Court puts the “confusion” argument to bed

At that point, that all sounded very positive for BBB. However, the Court noted (at [134]) that BBB’s 1994 mark contained a disclaimer. When BBB’s 1994 mark was registered under the former Trade Marks Act 1953 (NZ), section 23 allowed the Commissioner to require any elements of a trade mark to be disclaimed that are common to the trade or otherwise non-distinctive. BBB’s 1994 mark disclaimed the words “bed” and “bath”.

While BBB does not sell baths or beds, those words are highly descriptive, or “elliptically descriptive” of the character of BBB’s retail services and of the products they sell. This is important because confusion from descriptive elements is less relevant (at [149]). The Court quoted the decision in Office Cleaning Services Ltd v Westminster Window and General Cleaners [1946] 1 All ER 320:

“So long as descriptive words are used by two traders as part of their respective trade names, it is possible that some members of the public will be confused whatever the differentiating words may be … It comes in the end, I think, to no more than this, that where a trader adopts words in common use for his trade name, some risk of confusion is inevitable. But that risk must be run unless the first user is allowed unfairly to monopolise the words. The Court will accept comparatively small differences as sufficient to avert confusion. A greater degree of discrimination may fairly be expected from the public where a trade name consists wholly or in part of words descriptive of the articles to be sold or the services to be rendered.”

Use of descriptive and non-distinctive words

The Court summarised (at [153]) by saying that “the use in a trade mark of descriptive/non-distinctive words lessens the risk of vitiating or fatal confusion — notwithstanding the higher likelihood of similarity with other marks.”

Expanding on its reasoning, the Court stated that “some confusion must be expected and tolerated as the price for using such words” and that their use “diminishes the capacity of the relevant marks to signify the relevant origin of the goods or services to which they relate.”

The decision culminated in the Court’s conclusion that “reasonable consumers confronted with such marks will recognise the descriptive allusions for what they are and are understand that they are less likely to signal a connection with the particular proprietor of the mark, or the proprietor’s goods and services.”

The Court also cited that small differences, such as “&” and “N’” or “beyond” and “table” could act as sufficient distinguishing factors between the marks.

Accordingly the Court rejected the invalidity claim based on section 25(1)(b), as in this case any confusion came from shared non-distinctive or descriptive words (at [174]).

The takeaway

When a trade mark is dominated by non-distinctive or descriptive elements, the ability to enforce that trade mark against other similar trade marks is going to be more limited. In particular, a business cannot hope to prevent its competitors from using those same non-distinctive or descriptive elements in their trade marks if they are common industry terms.

That lesson applies outside New Zealand as well. Strong trade marks are distinctive and not based on signs that other traders have a legitimate interest in using. It’s those strong, distinctive marks that give maximum protection to your business’ branding and the ability to protect it from imitators and look-alikes.

The Macpherson Kelley IP team can assist you with trade mark registration in Australia and New Zealand and provide you with wide-ranging IP advice. Including whether your desired trade mark is distinctive.

Note: The New Zealand “Bed Bath & Beyond” business is not related to the US “Bed Bath & Beyond” business that is owned by Liberty Procurement Co Ltd.

The information contained in this article is general in nature and cannot be relied on as legal advice nor does it create an engagement. Please contact one of our lawyers listed above for advice about your specific situation.

stay up to date with our news & insights

Battle of the beds and baths in New Zealand trade marks

Did you know that you can contest the validity of a competing trade mark if you believe the mark shouldn’t have been registered in the first place? In New Zealand, the Court or Commissioner has the power to decide whether a trade mark is invalid and therefore, should be treated as unregistered. This can be a worthy tactic for protecting your brand, but there are specific considerations that may hinder your chance at a successful outcome, as demonstrated by a recent dispute.

Bed Bath & Beyond lost its fight to have Bed Bath ‘N’ Table’s registered trade mark invalidated in New Zealand. The High Court of New Zealand handed down its decision in Brands Limited v Bed Bath ‘N’ Table Pty Limited [2023] HZHC 1766 on 7 July 2023.

Bubble, bubble, toil and trouble

Both Bed Bath & Beyond (BBB) and Bed Bath ‘N’ Table (BBT) have operated in New Zealand in parallel for over 15 years. Both brands sell furniture, linen and home décor, using similar green branding.

There were two rounds of trade mark registrations.

The first, in 1994. BBB registered the trade mark “BED BATH & BEYOND”; BBT applied 5 months later to register “BED BATH N’ TABLE” but ended up abandoning those applications.

The second, in 2014. Both BBB and BBT again applied to register their respective trade marks. By this stage, BBB had 51 stores in NZ and BBT had 9 (plus 97 in Australia). On 4 June 2014, BBT applied to register “BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE” in NZ and 5 days later BBB filed its own application for “BED BATH & BEYOND” in respect of very similar goods. Both parties’ marks were registered without opposition from the other.

The trade mark dispute commences

In 2018, BBT opposed BBB’s application to register “BED BATH & BEYOND” in Australia. Included in BBT’s evidence was a claim that the use of “BED BATH & BEYOND” would lead to consumer confusion.

In December 2018, BBB sought cancellation of BBT’s trade mark registration in New Zealand under section 73 of the Trade Marks Act 2002 (NZ), on the basis of invalidity. That is, if the trade mark should not have been validly registered, then it should not be allowed to remain on the register. Claims for trade mark infringement, passing off and fair trading claims were added in 2020, but we’ll focus on the invalidity claim here.

The invalidity claim

Under section 73, the Court, on the application of an aggrieved person, may declare the registration of a trade mark invalid to the extent that it was not registrable. Under section 74, an invalid mark is treated as if it had not been registered.

At the core of BBB’s claim was section 25(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 2002 (NZ) which discusses reasons the Commissioner should not register a trade mark in respect of any goods or services.

The core issues arising for determination under s 25(1)(b) were:

- whether BBT’s 2014 trade mark was registered in respect of goods or services that are the same as or similar to those covered by BBB’s trade mark;

- whether BBT’s 2014 trade mark was similar to BBB’s trade mark; and

- whether the fair notional use of BBB’s trade marks and BBT’s 2014 trade mark is likely to deceive or confuse a substantial number of persons in the relevant market.

Similar goods and services?

BBB could only rely on its much narrower 1994 registration rather than its broader 2014 registration which post-dated BBT’s 2014 registration. It meant that the respective goods and services being compared were:

- BBB’s 1994 registrations that covered former class 42; and

- BBT’s 2014 registration which included class 20, 24 and 35.

The comparison of goods and services are detailed in the table below.

In comparing these goods and services, the Court held (at para [121]) that the services in class 35 of BBT’s application and many of the goods in class 24 are similar to the services in BBB’s registration. Even though BBB’s earlier mark was only registered in relation to services, these services were still similar to BBT’s goods, much like the Australian concept of goods that are “closely related” to services.

Confusingly similar marks?

The assessment of trade mark similarity is based on “an assessment of the fair and notional use” of the trade marks, not their actual use.

The threshold for “confusion” between two trade marks is lower than “deceived”. “Confusion” may go no further than perplexing or mixing up the minds of the purchasing public, while “deceived” requires an incorrect belief.

The High Court set out the considerations, based on the earlier decision of the New Zealand Court of Appeal in Pharmazen Ltd v Anagenix IP Ltd [2020] NZCA 306 at [47]:

(a) the Court should consider the marks in their entirety; the overall or net impression of the marks should be considered;

(b) while differences between two marks may be significant, it is the similarities which are most significant, whether visual, audible, distinctive, or conceptual;

(c) the impression or idea conveyed by the marks is important in assessing how they will be recalled; the idea of a mark is more likely to be recalled than its precise details;

(d) comparison is not of the opponent’s mark with the mark of the applicant when taken side by side, but taking into account imperfect recollection in all the circumstances in which the products might be sold; and

(e) the marks are to be compared as they would be encountered in the usual circumstances of trade.”

In the words of the Court in the BBB / BBT case:

(a) both marks begin with the alliteratively memorable combination of words: “bed, bath”;

(b) in both marks, the words “bed” and “bath” are used not in a directly descriptive way (discussed further below) but in what is known as an indirectly descriptive way;

(c) in other words, each mark indirectly refers to the products sold by the trade mark owner—products for the bedroom and products for the bathroom;

(d) in BBB’s mark the words “bed, bath” are followed by “’n”, which undoubtedly signifies “and”;

(e) in BBT’s mark the words “bed, bath” are followed by “and”;

(f) in BBB’s mark the words “bed, bath ‘n” are followed by the two syllable, word “beyond”;

(g) in BBT’s mark the words “bed, bath and” are followed by the two syllable word “table”;

(h) just as the word “beyond” reinforces the alliterative flavour of the BBB mark as a whole, the second syllable of “table” (“ble”) reinforces the alliterative flavour of the BBT mark as a whole;

(i) in the context of BBB’s mark, the word “beyond” is intended to refer, and would reasonably be construed as alluding to, “goods for use in other rooms in a house”;

(j) in the context of BBT’s mark, the word “table” is intended to refer, and would reasonably, be construed as alluding to “goods for use in the kitchen and/or dining room”;

(k) reading all the words in BBB’s mark together, they convey the impression or idea of “goods for use in the home”;

(l) reading all the words in BBT’s mark together, they convey the impression or idea of “goods for use in the home”;

(m) there is therefore considerable visual (four words, the first three of which are effectively identical and in identical order) and aural (four words, the first three of which are effectively identical and the last of which has two syllables) similarity between the two marks; and

(n) the marks are likely to be encountered in similar circumstances (retail outlets operated by the parties, and the branding and advertising of the goods sold there).

Court puts the “confusion” argument to bed

At that point, that all sounded very positive for BBB. However, the Court noted (at [134]) that BBB’s 1994 mark contained a disclaimer. When BBB’s 1994 mark was registered under the former Trade Marks Act 1953 (NZ), section 23 allowed the Commissioner to require any elements of a trade mark to be disclaimed that are common to the trade or otherwise non-distinctive. BBB’s 1994 mark disclaimed the words “bed” and “bath”.

While BBB does not sell baths or beds, those words are highly descriptive, or “elliptically descriptive” of the character of BBB’s retail services and of the products they sell. This is important because confusion from descriptive elements is less relevant (at [149]). The Court quoted the decision in Office Cleaning Services Ltd v Westminster Window and General Cleaners [1946] 1 All ER 320:

“So long as descriptive words are used by two traders as part of their respective trade names, it is possible that some members of the public will be confused whatever the differentiating words may be … It comes in the end, I think, to no more than this, that where a trader adopts words in common use for his trade name, some risk of confusion is inevitable. But that risk must be run unless the first user is allowed unfairly to monopolise the words. The Court will accept comparatively small differences as sufficient to avert confusion. A greater degree of discrimination may fairly be expected from the public where a trade name consists wholly or in part of words descriptive of the articles to be sold or the services to be rendered.”

Use of descriptive and non-distinctive words

The Court summarised (at [153]) by saying that “the use in a trade mark of descriptive/non-distinctive words lessens the risk of vitiating or fatal confusion — notwithstanding the higher likelihood of similarity with other marks.”

Expanding on its reasoning, the Court stated that “some confusion must be expected and tolerated as the price for using such words” and that their use “diminishes the capacity of the relevant marks to signify the relevant origin of the goods or services to which they relate.”

The decision culminated in the Court’s conclusion that “reasonable consumers confronted with such marks will recognise the descriptive allusions for what they are and are understand that they are less likely to signal a connection with the particular proprietor of the mark, or the proprietor’s goods and services.”

The Court also cited that small differences, such as “&” and “N’” or “beyond” and “table” could act as sufficient distinguishing factors between the marks.

Accordingly the Court rejected the invalidity claim based on section 25(1)(b), as in this case any confusion came from shared non-distinctive or descriptive words (at [174]).

The takeaway

When a trade mark is dominated by non-distinctive or descriptive elements, the ability to enforce that trade mark against other similar trade marks is going to be more limited. In particular, a business cannot hope to prevent its competitors from using those same non-distinctive or descriptive elements in their trade marks if they are common industry terms.

That lesson applies outside New Zealand as well. Strong trade marks are distinctive and not based on signs that other traders have a legitimate interest in using. It’s those strong, distinctive marks that give maximum protection to your business’ branding and the ability to protect it from imitators and look-alikes.

The Macpherson Kelley IP team can assist you with trade mark registration in Australia and New Zealand and provide you with wide-ranging IP advice. Including whether your desired trade mark is distinctive.

Note: The New Zealand “Bed Bath & Beyond” business is not related to the US “Bed Bath & Beyond” business that is owned by Liberty Procurement Co Ltd.