ESG claims in marketing and advertising – it’s gotta come out in the (green)wash

These days, consumers are demanding more sustainable products from brands – and are often happy to pay more for them. Employees are also expecting their employers to act in an ethical manner, placing value on the greater purpose of their role and the impact of the businesses they work for. Amongst all these demands, businesses are trying to differentiate themselves from their competitors.

A consequence of the current times, the collective rise in “Environmental”, “Social” and “Governance” (ESG) conscience has seen “Green” claims in business advertising rise, and along with it, a regulatory focus on “Greenwashing”.

What is greenwashing?

“Greenwashing” occurs when a business is misleading or deceptive, or overrepresents the extent to which its products, services or practices are environmentally friendly, sustainable or ethical.

Where can greenwashing occur?

Whether conduct is, in fact, misleading or deceptive will always come down to the specific circumstances of each individual case. What was communicated, how it was communicated, what disclaimers (if any) were used, whether language or imagery has a particular common vs technical meaning, what consumers would have understood to be conveyed, must all be considered.

But as a guide, misleading or deceptive conduct can often occur in the following common scenarios:

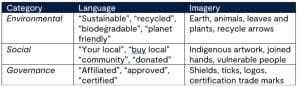

1. ESG “credence” claims: Language or imagery invoking authority, credibility or other characteristics. Such as:

2. “Absolute” claims: Claims and statements that are absolute, infer absolute fact, and give no ‘wriggle room’ (eg, ‘100% recycled’, ‘no plastic’, etc).

3. Vague claims: Claims and statements that are vague, unqualified or inadequately qualified (eg, “low emissions”, “sustainable”, “ocean friendly”). Also within this remit are claims and statements that perhaps cannot be substantiated at all (eg, “green”), and/or where no or little explanation is given about what the terms actually mean in technical industry jargon vs common parlance (eg, “light”, “mild”, “supporting your community”).

4. Qualifiers and disclaimers: “Fine print” that overrides, undermines or completely reverses the prominent headline message. Such as:

5. Aspirational claims: Setting goals that cannot be measured, or which cannot be achieved in either the manner or timeframe stated (eg, “100% recyclable by 2025”). This also includes setting goals but not achieving them (and/or showing no progress towards achieving them).

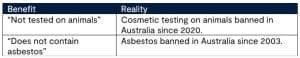

6. Irrelevant claims: Exaggerating certain characteristics for consumer benefit, in circumstances where the benefit is not a particular business feature, eg:

7. Hidden trade offs: Emphasising a positive characteristic whilst down-playing other, potentially more damaging characteristics. Such as:

8. Counter-intuitive activities: Initiatives and activities that seem sustainable but are not (eg, designing a new fast food “straw-less lid”, which actually contains more plastic than the old lid-and-straw combination).

9. Lesser of two evils: The claim or representation is true, but a greater risk of environmental, health or social impact prevails (eg, “organic cigarettes”).

10. Silence or omission: Finally, being silent or omitting key information can also be misleading or deceptive (eg, offsetting carbon emissions for only the first year of a motor vehicle’s life, or excluding investments in tobacco at only one tier of the supply chain).

What are practical tips for businesses?

- As a starting point – use common sense! If you think your advertising is too sharp or tricky… It probably is.

- Be transparent and specific – make clear what ESG benefit your product/service offers.

- Beware of industry jargon (eg, double meanings, overly technical language).

- Consider your marketing style and appetite in the context of community and customer expectations in your industry.

- Consider the entire lifecycle of your products and/or services (and not just the first year, or first use).

- Verify the accuracy of your marketing statements against your actual business activities and entire business footprint – a “whole of business” approach.

- Substantiate your sustainability statements with facts (test reports, scientific reports, data, supply chain information, third party certification, etc).

- Beware of qualifiers and disclaimers. They should only refine the headline message (not re-write it).

- Update your marketing materials as your business, its activities and its commitments change.

- Train your staff.

- Think like a consumer – be prepared to answer questions and complaints.

- Think like a regulator – be prepared to defend or substantiate the claims you make.

You can read our earlier publications about greenwashing here and here.

For further information and advice about your advertising obligations, or for a review of your marketing campaigns and collateral, or to help you defend Regulator requisitions, please contact the experts at Macpherson Kelley.

The information contained in this article is general in nature and cannot be relied on as legal advice nor does it create an engagement. Please contact one of our lawyers listed above for advice about your specific situation.

more

insights

stay up to date with our news & insights

ESG claims in marketing and advertising – it’s gotta come out in the (green)wash

These days, consumers are demanding more sustainable products from brands – and are often happy to pay more for them. Employees are also expecting their employers to act in an ethical manner, placing value on the greater purpose of their role and the impact of the businesses they work for. Amongst all these demands, businesses are trying to differentiate themselves from their competitors.

A consequence of the current times, the collective rise in “Environmental”, “Social” and “Governance” (ESG) conscience has seen “Green” claims in business advertising rise, and along with it, a regulatory focus on “Greenwashing”.

What is greenwashing?

“Greenwashing” occurs when a business is misleading or deceptive, or overrepresents the extent to which its products, services or practices are environmentally friendly, sustainable or ethical.

Where can greenwashing occur?

Whether conduct is, in fact, misleading or deceptive will always come down to the specific circumstances of each individual case. What was communicated, how it was communicated, what disclaimers (if any) were used, whether language or imagery has a particular common vs technical meaning, what consumers would have understood to be conveyed, must all be considered.

But as a guide, misleading or deceptive conduct can often occur in the following common scenarios:

1. ESG “credence” claims: Language or imagery invoking authority, credibility or other characteristics. Such as:

2. “Absolute” claims: Claims and statements that are absolute, infer absolute fact, and give no ‘wriggle room’ (eg, ‘100% recycled’, ‘no plastic’, etc).

3. Vague claims: Claims and statements that are vague, unqualified or inadequately qualified (eg, “low emissions”, “sustainable”, “ocean friendly”). Also within this remit are claims and statements that perhaps cannot be substantiated at all (eg, “green”), and/or where no or little explanation is given about what the terms actually mean in technical industry jargon vs common parlance (eg, “light”, “mild”, “supporting your community”).

4. Qualifiers and disclaimers: “Fine print” that overrides, undermines or completely reverses the prominent headline message. Such as:

5. Aspirational claims: Setting goals that cannot be measured, or which cannot be achieved in either the manner or timeframe stated (eg, “100% recyclable by 2025”). This also includes setting goals but not achieving them (and/or showing no progress towards achieving them).

6. Irrelevant claims: Exaggerating certain characteristics for consumer benefit, in circumstances where the benefit is not a particular business feature, eg:

7. Hidden trade offs: Emphasising a positive characteristic whilst down-playing other, potentially more damaging characteristics. Such as:

8. Counter-intuitive activities: Initiatives and activities that seem sustainable but are not (eg, designing a new fast food “straw-less lid”, which actually contains more plastic than the old lid-and-straw combination).

9. Lesser of two evils: The claim or representation is true, but a greater risk of environmental, health or social impact prevails (eg, “organic cigarettes”).

10. Silence or omission: Finally, being silent or omitting key information can also be misleading or deceptive (eg, offsetting carbon emissions for only the first year of a motor vehicle’s life, or excluding investments in tobacco at only one tier of the supply chain).

What are practical tips for businesses?

- As a starting point – use common sense! If you think your advertising is too sharp or tricky… It probably is.

- Be transparent and specific – make clear what ESG benefit your product/service offers.

- Beware of industry jargon (eg, double meanings, overly technical language).

- Consider your marketing style and appetite in the context of community and customer expectations in your industry.

- Consider the entire lifecycle of your products and/or services (and not just the first year, or first use).

- Verify the accuracy of your marketing statements against your actual business activities and entire business footprint – a “whole of business” approach.

- Substantiate your sustainability statements with facts (test reports, scientific reports, data, supply chain information, third party certification, etc).

- Beware of qualifiers and disclaimers. They should only refine the headline message (not re-write it).

- Update your marketing materials as your business, its activities and its commitments change.

- Train your staff.

- Think like a consumer – be prepared to answer questions and complaints.

- Think like a regulator – be prepared to defend or substantiate the claims you make.

You can read our earlier publications about greenwashing here and here.

For further information and advice about your advertising obligations, or for a review of your marketing campaigns and collateral, or to help you defend Regulator requisitions, please contact the experts at Macpherson Kelley.