Is it a Big Mac? Is it a Big Jack? … no it’s a Big MacJac!

Australia’s burger wars have heated up again with McDonald’s threatening trade mark infringement proceedings against Rashays (an Australian restaurant chain) who’ve released their Big MacJac burger.

It comes after McDonald’s took action against rival Hungry Jacks over its Big Jack, claiming it infringed the McDonald’s Big Mac.

Now along comes the Big MacJac comprising “two all [wagyu] beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions on a sesame seed bun”. Sound familiar? It should as that’s the identical ingredients (except for a different type of beef) to the Big Mac, and incidentally the Big Jack.

Rashjays claims the burger was created with the intention of being tongue-in-cheek to poke fun at the bun fight between McDonald’s and Hungry Jacks.

Courtesy: Hungry Jack’s / McDonald’s/ @bengrahamjourno

McDonald’s is looking to enforce its trade mark rights in its ‘Big Mac’ trade mark that it’s held since 1973. This may be difficult for the fast food giant.

This naming rights issue aside, the real issue at play is that McDonald’s doesn’t want identical burgers to the Big Mac in the market.

The image above shows the striking similarity between the appearance of the three burgers, which leads to the bigger (and more pertinent) question that needs to be asked: what IP protection strategy is McDonald’s adopting?

They’ve “dropped the bun” on more than one occasion when it comes to protecting their iconic Big Mac throughout the world, and now it appears that they may have numerous copycat burgers being served up all over Australia.

the shape of things to come

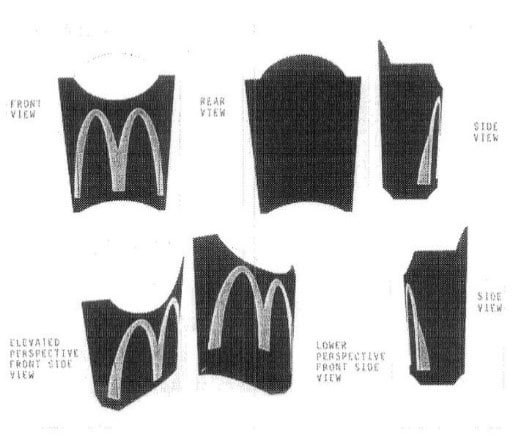

In 2002 McDonald’s sought protection of their fries’ box, shown below, as a shape trade mark (being their only ever Australian shape trade mark). This was a great move to protect an iconic symbol of McDonalds, but it makes you wonder why they didn’t also seek to protect the look of the Big Mac at the same time.

Courtesy: IP Australia Trade Mark Database

In 2002 the Big Mac was instantly recognisable and was distinct to every other burger on the market. An image of the ‘triple’ bun would (with nothing more) instantly associate that burger with McDonalds – in short, the Big Mac acted as a trade mark for McDonalds in and of itself.

Accordingly, an application for the shape of the Big Mac burger would have been likely to attain registration – most likely based on evidence of use demonstrating it had become distinctive of McDonald’s.

This wasn’t done and now it’s unlikely (in light of the basket of similar buns in the market) McDonald’s could still lay claim to the shape of a Big Mac burger as acting as a trade mark to distinguish their burger from others.

This is unfortunate for McDonald’s as a shape trade mark would have been an extremely useful weapon in this fast feud. In particular, it would have been extremely difficult for Hungry Jack’s to argue that the use of the burger image didn’t infringe McDonald’s trade mark rights, as McDonald’s could argue that a consumer would be caused to wonder whether there was some authorisation from McDonald’s to allow Hungry Jack’s to make and sell the Big Jack.

The subtle changes in the positioning of the ingredients would be unlikely to be noticed by a consumer looking at an image of the burger, and so it’d be likely confusion could be established at law.

However, the absence of a shape trade mark places a greater reliance on the word marks and the respective reputations of McDonald’s in ‘Mac’ and Hungry Jack’s in ‘Jack’. It’s evident that the changing of the ‘M’ to a ‘J’ and the addition of a ‘K’ is highly distinctive and instantly noticeable to consumers given the fame of these respective burger franchises.

Accordingly, McDonald’s is all but destined to lose this trade mark infringement battle.

It’ll be interesting to see whether McDonald’s (and other owners of iconic symbols) use this as a call to action to protect their trade dress rights through shape trade marks.

This article first appeared on WTR Daily, part of World Trademark Review, in October 2020. For further information, please go to www.worldtrademarkreview.com

The information contained in this article is general in nature and cannot be relied on as legal advice nor does it create an engagement. Please contact one of our lawyers listed above for advice about your specific situation.

more

insights

A change of director can trigger landholder duty says Victorian Supreme Court

Clarifying the boundaries of trade mark defences: The Fanatics case as a cautionary tale

PPS refresher: Key risks and exposures for agribusinesses in 2026

stay up to date with our news & insights

Is it a Big Mac? Is it a Big Jack? … no it’s a Big MacJac!

Australia’s burger wars have heated up again with McDonald’s threatening trade mark infringement proceedings against Rashays (an Australian restaurant chain) who’ve released their Big MacJac burger.

It comes after McDonald’s took action against rival Hungry Jacks over its Big Jack, claiming it infringed the McDonald’s Big Mac.

Now along comes the Big MacJac comprising “two all [wagyu] beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions on a sesame seed bun”. Sound familiar? It should as that’s the identical ingredients (except for a different type of beef) to the Big Mac, and incidentally the Big Jack.

Rashjays claims the burger was created with the intention of being tongue-in-cheek to poke fun at the bun fight between McDonald’s and Hungry Jacks.

Courtesy: Hungry Jack’s / McDonald’s/ @bengrahamjourno

McDonald’s is looking to enforce its trade mark rights in its ‘Big Mac’ trade mark that it’s held since 1973. This may be difficult for the fast food giant.

This naming rights issue aside, the real issue at play is that McDonald’s doesn’t want identical burgers to the Big Mac in the market.

The image above shows the striking similarity between the appearance of the three burgers, which leads to the bigger (and more pertinent) question that needs to be asked: what IP protection strategy is McDonald’s adopting?

They’ve “dropped the bun” on more than one occasion when it comes to protecting their iconic Big Mac throughout the world, and now it appears that they may have numerous copycat burgers being served up all over Australia.

the shape of things to come

In 2002 McDonald’s sought protection of their fries’ box, shown below, as a shape trade mark (being their only ever Australian shape trade mark). This was a great move to protect an iconic symbol of McDonalds, but it makes you wonder why they didn’t also seek to protect the look of the Big Mac at the same time.

Courtesy: IP Australia Trade Mark Database

In 2002 the Big Mac was instantly recognisable and was distinct to every other burger on the market. An image of the ‘triple’ bun would (with nothing more) instantly associate that burger with McDonalds – in short, the Big Mac acted as a trade mark for McDonalds in and of itself.

Accordingly, an application for the shape of the Big Mac burger would have been likely to attain registration – most likely based on evidence of use demonstrating it had become distinctive of McDonald’s.

This wasn’t done and now it’s unlikely (in light of the basket of similar buns in the market) McDonald’s could still lay claim to the shape of a Big Mac burger as acting as a trade mark to distinguish their burger from others.

This is unfortunate for McDonald’s as a shape trade mark would have been an extremely useful weapon in this fast feud. In particular, it would have been extremely difficult for Hungry Jack’s to argue that the use of the burger image didn’t infringe McDonald’s trade mark rights, as McDonald’s could argue that a consumer would be caused to wonder whether there was some authorisation from McDonald’s to allow Hungry Jack’s to make and sell the Big Jack.

The subtle changes in the positioning of the ingredients would be unlikely to be noticed by a consumer looking at an image of the burger, and so it’d be likely confusion could be established at law.

However, the absence of a shape trade mark places a greater reliance on the word marks and the respective reputations of McDonald’s in ‘Mac’ and Hungry Jack’s in ‘Jack’. It’s evident that the changing of the ‘M’ to a ‘J’ and the addition of a ‘K’ is highly distinctive and instantly noticeable to consumers given the fame of these respective burger franchises.

Accordingly, McDonald’s is all but destined to lose this trade mark infringement battle.

It’ll be interesting to see whether McDonald’s (and other owners of iconic symbols) use this as a call to action to protect their trade dress rights through shape trade marks.

This article first appeared on WTR Daily, part of World Trademark Review, in October 2020. For further information, please go to www.worldtrademarkreview.com